Richmond 1927

Chapter 1

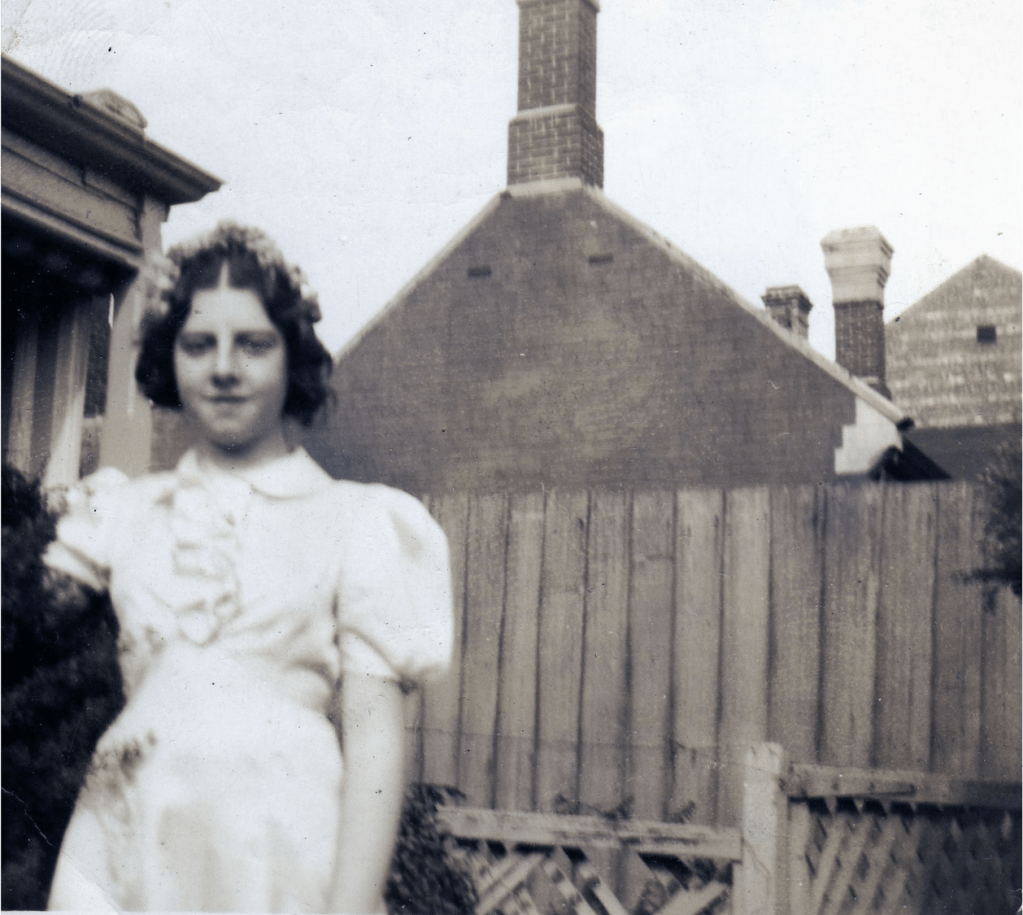

Richmond July, 1927

Bessie was called early that morning to Griffith Street. It was a cold, wet July morning; streaking the dawn with grubby squalls that squealed along failing fence palings as the early horse and jinker of the milkie tumbled over the broken ruts of the Richmond streets. May was silent but quick to labour, and only an hour or two after her older girls left for school, a dark-haired baby appeared – a girl like her older sisters; tiny, angry and yowling. She bellowed frantically, as Bessie, the woman of her clan that was responsible for birthing all the babies, cleaned and wrapped her in a grey, wollen blanket; a mass of black hair cresting her scrunched brow. May Redding had lost track of the time, it had just been her, the pain, the moribund midwife and the sound of scattered footsteps on the late morning streets forever. She dozed, waking bleakly to the sound of the front door and excited footsteps of Eileen and Lorna.

Usually the girls did not walk home together. They preferred to wait and let the other leave the rain potted school yard before them, chatting with their own friends on the walk home. If there were no friends who tagged along, the omnipresent magpies were preferred company to each other. However, this day, they called a truce on their estrangement ritual, and rushed home together through the wind lashed terraces to their own street for news of the little one. Bessie informed them of the stark fact that no little brother had been forthcoming, and they tiptoed down the hallway firing questions to her and each other about names and when they could view their new sister.

May was disappointed it wasn’t a son. It could have made up for this unsought surprise so late in her life, when her other daughters were almost out of school themselves and off to work. Yet holding her some time later, May noticed her round sweet mouth, and wet, tiny sighs and she thought her prettier than the other girls from what she could remember. There was a sad, glazed look in the little one’s eyes as she looked desperately around the room for a familiar sound or warming shade. Bessie had wrapped her tightly and put her in the tiny basket, wedged against the wall of the scrappy room.

A few small hours she was spared the crying of the newborn, and then the shouting started. Like a shock of cold water, the new life howled at the night, and foraged for whatever food it could get. Some evaporated milk in the kitchen was heated by Bessie and it seemed to soothe the baby and keep it quiet. All May wanted to do was sleep.

It must have been evening again before steps appeared suddenly in the hallway and it was her husband Arthur. He was a few years older than May and his thick head of hair had begun to grey lightly; his once handsome face had taken on a wary, averted gaze and it seemed his eyes had receded behind his eyelids to protect his soul from the light. This night however his voice was strangely clear and jolly.

‘You have another girl!’ Bessie consoled Arthur. It must have behoved even him not to go back to the pub after work, with the expectation of news of his third child’s birth. The celebrations would be saved to the following evening instead. Bessie had the baby warm, clean and wrapped and gave her to May. Arthur appeared vaguely at the door and restated the instruction he received.

‘Seems like we got another baby girl.’ He looked uncomfortable, a little sheepish in his sober-ish mantel. ‘What sort of name do you like May? Have you named her?’

‘Shirley …Shirley Kathleen.’

Shirley was a pretty name, and Kathleen after his sister back home. The baby kept looking at the dark from her basket and seeing shadows moving glazed, into light.

Lorna and Eileen fussed over the baby and would fight over who would nurse her first as soon as they returned home from school. Looking down at the tiny sack, warm and squirming, her musky smell moving around them like a mist, they were intrigued. Their mother spent a week lying in a darkened room and when she appeared eventually, it was much to everyone’s relief. Arthur would return home at 6.30 after last swill at the pub, and if the baby was awake, and he was in a good mood, he would coo over her briefly before he retired to the front room.

When May first suspected she was in the family way, she flatly refused to consent that it could be possible. Each day, she would convince herself that this was not reality and go about her housework, or head out to do the errands. On Friday each week, she would brush down her summer coat and polish her new shoes and head into town before 9 am so that she could be there in time for the stores to open. Each day she would choose a few of her favourite stores and window shop for hours. Occasionally she would see something so rare and beautiful – a dress perhaps, or a pair of gloves…a new hat – brogues – a scarf that was the colour of wheat. She would then take herself in to admire this exquisite piece and spend the next two months working out how she could scrimp and save what was needed to put a layby deposit down on it. May would work out her limited budget over and over again, convinced she could find some new tiny amount that could go towards her dream outfit. Eventually the house had no butter, only a few treasured pieces of bread that survived each day, and an empty pantry that whistled with the sound of starving cockroaches.

However she managed it, (the housekeeping was never enough for the four of them already) she always bought home whatever it was she had set her heart on. Hats from Dugdale’s on Collins Street, leather gloves from Stanton’s, a suit from Greville’s in Spring Street – grey with a black inset, and pleated peplums. Shoes were the most lavish purchase; dainty brown leather heels with pointed toes and elegant satin bows from the Paragon Shoe Store in Elizabeth Street.

The pregnancy had eventually forced her into her simple work clothes with the darts let out. May refused to plan for the child, but luckily her sisters and Arthur’s mother began knitting and sending small parcels of nighties, booties and shawls. Her and Arthur rarely spoke, but she silently hated him for what he had done. It was all right for him to retire to his library in the front room with his whisky and his books. She watched the Winter creep relentlessly across the backyard and the rusted outhouse. Slowly, a horse and jinker rattled past. May thought it made the loneliest sound in the world.

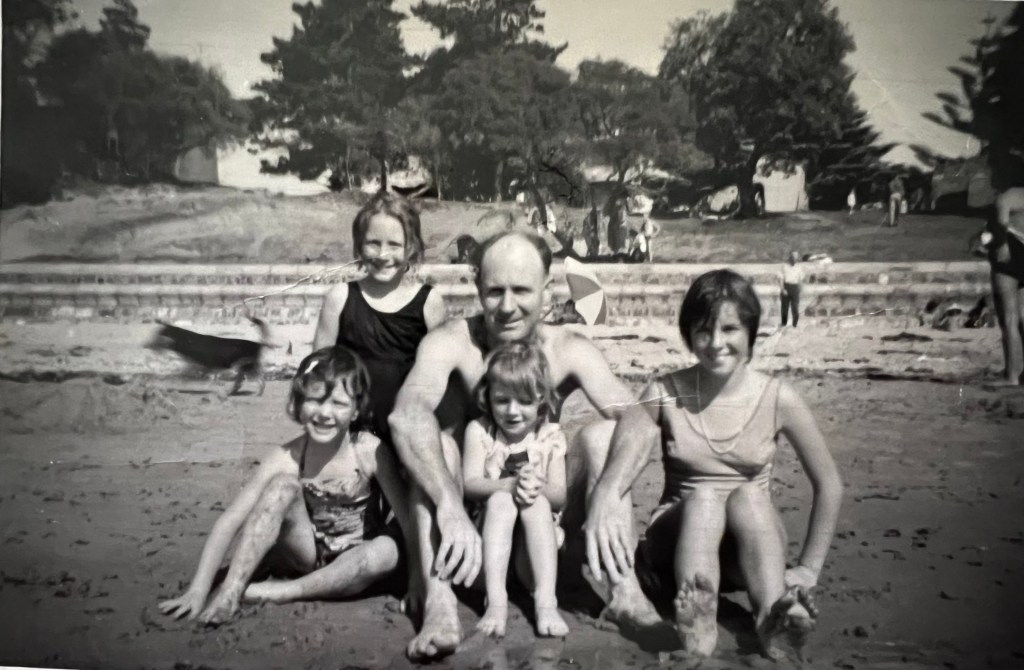

Summer 1968

It’s Sunday at last.

When Dad announced at the tea table on Thursday after dinner that Sunday looked like being hot, and we were going to the beach, I jumped out of my seat and yelled HOORAY!

In celebration, I raced out of the front door after dinner. It was light and warm, with a hazy dusk of summer flowers. I told my exciting news of a trip to Rosebud on Sunday to every neighbourhood kid I could find. They were sometimes puzzled at my excitement, but mostly they were jealous.

Friday was such a long day at school. My school dress felt fresh and cool in the morning shadows, but by lunchtime my legs were sticking to the benches at school, and the air crawling through the rattling, classroom window hoarsely foreshadowed the weekend heat wave wind ahead.

Saturday went by even slower. The street was glazed with blazing concrete, and the rose bushes shrivelled against forlorn front fences. No one moved through the long suburban afternoon except bored children, and sullen cats. The thought of the beach the next day was a dream. As the cool evening breeze finally floated through the front door and the open windows, the neighbourhood sprinklers starting ticking and darting down the street, and Mum and Dad set out the esky and the boxes packed with food to take the next morning. We were leaving very early to complete our slow trek down the Nepean Freeway before the heat really set in, so everything needed to be ready to grab and go. The kitchen looked and smelt like a beach day picnic already.

I went to bed that night with my towel, bathers and beach dress draped carefully at the bottom of my bed. I could barely get to sleep thinking about the crystal, cold ocean. My dreams were full of gentle, wind flecked waves.

I woke up when it was just getting light, and jumped up to start on some breakfast. Jill was already up and soon the others appeared; Mum with the baby Carolyn, Dad and my older sisters: Kathryn, Helen. After gulping down my cornflakes, I threw on my bathers and my towelling beach dress with the front zip that Santa bought me, and I was ready. While the big girls chatted in their room, and the boxes were packed into the car, Jill and I ran deliriously up and down the driveway, and then burst out into the quiet, morning street. At Rigden’s, I could see Jane in the front window watching television. She waved at us. We ran back down to meet Noel from next door. We told him we were going to Rosebud, and he threw his ball at us. We screamed and threw it back, and went back to check the car again.

I didn’t think Mum and the big girls would ever stop doing everything. I skipped up the driveway and climbed on the front gate, and then went inside. I got in someone’s way, who growled at me, so I ran outside again.

Finally, Dad finished packing our white Holden station wagon boot with all our food for the picnic. Around the food were crammed beach bags, towels, hats, fold up chairs, our yellow and blue beach umbrella, and the esky full of cold drinks, cold meats, salad, and grapes. Boxes of biscuits, apples and apricots precariously rested on top.

After what seemed like forever, Mum along with the baby, Kathryn and Helen appeared, laden with floral beach bags – and everyone piled into the car. I sat in the front with Mum who had Carolyn in her lap, and the three bigger girls sat in the back seat. We pulled out of Parkstone Avenue – and we were on our way!

Slowly the city woke up around us, and we passed over the river, moving away from the big city buildings, snaking our way slowly along the bay through cheerful, sandy suburbs. The sun was heating up, and with all windows down we were feeling the growing glare of hot air funnelling on to our legs, and the sweat prickling and tickling our backs. The aching thirst for the seaside in my body was almost unbearable.

Jill and I always had a competition for who could see the ocean first. As I craned my neck and looked down each of the side streets, I felt so jealous of the kids who lived out here in these small, simple houses that hugged the beach roads.

Suddenly, it was there!! The startling blue of the cool, huge, sun-sparkling ocean snuck down the opening of one of the streets along Beach Road, and we were in sea land! Jill said she saw the water first, but I think she just wanted to win. I clapped and cheered anyway because I was so excited. I could smell the ocean – the salt, the waves, the seagulls crying! I could feel the spray and the sparkle, and almost hear the swimmers splashing through the hot wind rushing in the window. I just couldn’t wait!

Slowly, the front yards became taken over by tee trees, and the sand crept further up along the nature strips. We veered to the right and there we suddenly were; driving along the beach. I stuck my head out of the open window and smelt the salty, sea air. It was the air of last Summer, of freedom and happiness, of a cool escape from the scorching sun, and an endless, sparkling, peaceful playground. I was ready to explode with joy.

The exhausted car finally found a shady spot under the musky perfumed tee trees at Rosebud, serenaded by a few hot, lonely crickets. We unloaded our picnic blanket and boxes of food, and all of us ravenously attacked the bread rolls, packing them with our own selection from cold meats, cheese, lettuce, beetroot, tomatoes, pickles, jam, or vegemite. I had my favourite: meat and sauce, a cup of icy cordial, sweet sultana grapes, and some Savoury Shapes.

It was hard to concentrate on eating, as hungry as I was, as I could hear the squawking of excited seagulls and the tiny cries of children splashing, that floated through the glazed sand dunes. It made me fidget and jump around, wandering in and out of the nearby trees. The family ate quickly as we were all hot, and happy to get to the water.

Helping grab what we could from the car, including the baby’s toys, swim rings, foam surfboards and bucket and spades, our overladen crowd staggered over the sand trail through twigs buried secretly waiting to stab at our soles, around lines of ants scurrying in the sandy grass, in and out of tee tree shadows which gave way to hot, stinging sand, where dunes rose up to the azure ocean entrance in a blaze of sun, heat, wind and blue sky

We were finally at the beach!

Our feet slid through the footsteps of the tide as we surveyed the scene. We staked a large oval of uncrowded sand, and set up our camp for the day. The beach wasn’t busy yet, and the water was scattered with a sparse group of paddlers. I ran down to the water and felt it with my toes. The tide was out and the sand bars extended out for miles! Tiny specks of people near the horizon were only up to their waist. Mum called me back to put on my hat and some Coppertone, and told me not to get burnt.

We had to wait nearly an hour before swimming because those boys who drowned last Summer had not waited an hour after eating. It was agonising! I could splash around in the shallows which wasn’t hard at Rosebud, but all I wanted to do was dive down and see the world from beneath the water.

I kept asking Mum and Dad if it was time to go swimming yet, until finally they said “YES!”. I picked up my surfboard and ran with Jill to the water and kept running until we hit a deep hollow where we could swim underwater. It was so cold on my head after the hot, late morning sun. I dived and dived again. I held my breath and ducked under, opening my eyes. The sun streamed down into the water onto the sand ridges under the tiny waves making shady lace patterns. I dug my toes along the satin sand under the water, and felt the perfect, patterned ridges collapse. I watched tiny little holes in the sand breathe and move. I saw flickering schools of fishes, dart and flip, transparent against the sand. Overhead, the sky was a deep, bright blue with magical, shape shifting clouds that looked like dolphins and mermaids and fish. I jumped over the tiny, fairy waves and splashed the sunny air. I sank down to my neck and moved along on my hands, singing a little song about the ocean. I floated on my back, and rolled head over heels like an underwater acrobat. I collected shells, picking out the sweetest shapes, and traced the shoreline, kicking and flicking the water as far as it would go through the warm shallows.

After being in the water for a long time, I went back to land and helped Carolyn build a castle and a moat. I had something to eat again because I was starving. The big girls, shining with baby oil, were listening to their transistor radios, and sunbaking. Mum was watching the water out of the corner of her eye, and Jill sat beside her huddled in a towel.

The beach was full of people now. Little toddlers in frilly bikinis stumbled around whacking spades on the sand; chubby mums nursed babies at the water’s edge; dads pushed children upon surfboards out to the deeper water and groups of young men threw a tennis ball at each other splashing dramatically to catch it. Excited seagulls circled everywhere around lazy cricket games, and far off, outboard motorboats could be heard chuffing merrily around the bay.

The big excitement for the afternoon was when Mum and Dad came in for a swim. Dad would perform a dramatic run and silly dive, making us all laugh. Then he would blurt and back stroke, and grab the baby and take her for a swim as she squealed in delight.

Jill and I would line up for him to throw us out over the water and splash down out of control. It was so much fun! All too soon though, he would head back into shore.

Mum liked to stand in the shallows for ages, while we begged her to come in for a swim. Eventually she would sink into the water and rest on her back as she kicked along. We would swim up next to her, pretending to be baby dolphins diving around their mother, and we would squeal and giggle. She didn’t stay in the water very long either.

Carolyn loved splashing and filling up her bucket or sitting in the little waves and kicking her legs about. Then she would toddle up the beach to deposit a bucket of water in the hole dad dug for her, and wobble back to the water.

By late afternoon, I started to feel tired, and my eyes scratched with the sun. We sat under the umbrella sifting sand through our hands, until Dad called last swim.

We trudged back to the car in the tee trees, and I started to feel sunburnt, especially on my back and legs. We packed the hot, sticky car – my father insisting that every particle of sand was removed from our feet and flicked out of our towels before we clambered in. I sat in the back on the way home, and Jill got to sit in the front. We were all STARVING so we stopped in Frankston for fish and chips.

Mum divided up the chips and potato cakes between us on the newspaper, and we ate like we had not been fed in days. It tasted so good!

We set off for home, and as the beach turned back into the city, my shoulders and legs began to ache from the sunburn, and the sweaty plastic seats felt stuck to my salty, sandy legs. By the time we got home, my head was aching and my face was shining and red.

We jumped in the bath with the baby, and the bottom of the bath filled up with sand and tiny bits of seaweed. The warm water stung my red legs and back, but it still felt a bit better.

I climbed into my shortie pyjamas and went straight to bed. My eyes had almost closed by the time my head hit the pillow. During the night, turning over in bed, I could feel the hot, sunburn tearing at my skin. Yeow! I dreamed of swimming and darting with the fishes, and floating on my back in the blue.

The next morning, the air had changed, and it was cooler. When I put on my school dress, it hurt my back. I was burnt everywhere. That Coppertone hadn’t worked!

At school the kids laughed at my red legs, and teased me. They said I was as red as a lobster. But I didn’t care. None of them got to go to the beach yesterday. They had just been stuck at home in a heatwave, watching the midday movie or the cricket, trying to keep cool sitting in front of the fan with a wet face flannel.

I was lucky … I got to swim and play all day in the shimmering, cool, kind, vast, blue diamond ocean at Rosebud.

Chapter 20

When the War Is Over September 1945

There were great celebrations when it was announced that Germany had surrendered in the May, and the streets of Richmond, which were never short of men weaving their way between pub and bookie at any time of the day, were even more full of drunks wandering the streets, this time their faces full of sublime smiles, instead of the usual addled disappointment and despair. The Japs, however, were still being very stubborn in The Philippines where Fred’s ship HMAS Shropshire was stationed, so Shirley found it very hard to relax while everyone waited for that situation to improve. Fred’s letters were warm but circumspect, so it was hard to tell what was going on where he was. The announcements in early August of the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima caused a flurry of excitement at the front fences of Griffith Street once again, and the eventual surrender of the Japanese three weeks later in September was celebrated with great elation at the Milton’s house in Clark Street.

Some of the festivities were ruined a few days later when news arrived for one of Shirley’s Griffith Street neighbours. Betty Journeau, a single mother, had lived with her only son at Mrs Weston’s house three doors down for as long as Shirley could remember. Freddie was a friendly boy, a few years older than Shirley, but always up for a yarn when he ran into any of the Reddings. His mother idolised him, being just the two of them for so long after the disappearance of their father, who travelled up north one year for work and never returned. He had a lovely girlfriend, Lyla, who Shirley knew through the Children of Mary and the local dances.

Betty was a lonely figure when her son left for war in late 1944, and she wrote to him religiously every week, filling in the neighbours on all his latest news when she heard from him. Bringing some tea cake and Freddy’s most recent letters with her, she would often visit May – and the girls if they were home, for a cup of tea and a yarn on a Sunday afternoon. Bravely positive and intensely proud, Betty nonetheless fretted about her son and missed him prodigiously. Freddy and Shirley promised to write to each other when he left, and Shirley made sure to send him a letter to show that he was in all their thoughts, with a letter arriving back from him in good time, a few months after he left for New Guinea.

Not feeling much of a writer herself, Shirley had been tested with her letter composition skills, whilst corresponding so regularly with her Fred. Her joy about the time moving closer that Fred would return home safely was tempered the day the war before peace was declared in The Pacific, when upon returning home from work, her mother told her that she had heard from the neighbours that Betty had received a telegram that morning informing her that Freddie was killed on August 8th, ironically in between the two bombs that fell on Japan on the 6th and 9th of August, three weeks earlier.

It was hard to have much of a conversation with Betty a long time after that, and she wasn’t often seen out, even though the neighbours all made efforts to invite her in for a cup of tea as often as they could. Betty would occasionally appear, jaw set against the wind, head following her feet, on her way to the shops in Bridge Road. Shirley’s heart would sink at the sight. Eventually she returned to the occasional Sunday afternoon kitchen table chat, but it was a much quieter affair.

Shirley kept in touch with Betty until well after she moved away and started her own family. She would visit with the little girls and spend the afternoon talking about old times. The letter Freddy Journo wrote to her she kept safe until she died, crumpled, yellowed and ancient along with the other precious memorabilia she boxed up in her time capsule – place cards from her sister’s wedding, invitations to her own, telegrams from her dear friend Lorna for her 21st , baby cards, and bric-a-brac from a lifespan of tender moments, each carrying the patina of the joy, history and loss that make up the registry of life and death of each of our life’s journeys.

All things must pass – except the memories.

I hope that you enjoy reading the transcribed letter below. In a poignant coinidence, upon checking his records with the Australian War Memorial, I found out that Freddy’s name will be projected on to the exterior of Hall of Memory this Thursday evening 30th June at 6.06 pm. I wish as I often do, that Mum was still alive so I could tell her about it.

26th July 1945

Dear Shirley,

Your very welcome letter to hand and very pleased to hear from you, actually never expected to hear from you as you are really quite busy.

Sorry to hear that about your mother being off colour. Sincerely hope that by the time that you receive this she will be right.

The only reason that I am writing to you so promptly is we move up tomorrow to get into some more trouble, I guess that it will only last about three months, sincerely hope that it won’t be longer.

Your boyfriend certainly has been pretty quick with the mail, got to write to Lyla five or six times a week, but she writes that too, guess that I am too good to her, but she deserves it.

Lorna and husband certainly are doing their bit for the country, I guess that we will all have to start populating the country very shortly.

‘Holiday by the beach’ is a crackerjack show, I would love to see it and I agree that plays are the best.

Lately we have done nothing else but sleep and eat for about the last week or so- but agree that it does you good.

You would certainly enjoy yourself on the beaches up here, the surf is great, at times I guess that it is a pity that you are not here, but I guess that you would boost the morale too much if you paraded around the beach in your speedos.

Do you still do plenty of swimming or has the weather stopped you, actually it shouldn’t seeing that the baths are heated.

Well Shirley, actually will have to close, next letter, I will endeavour to tell you what we are doing.

Give my love to the family and Eileen and Lorna and yourself.

Love and Kisses

Fred

Freddy’s original letter below

Chapter Nineteen

Becoming Auntie Shirl

In early 1942, Shirley’s life was changed forever in a way that fate has of randomly picking up people’s lives and shaping them forever, just as the ocean washes a piece of reef off the beach and pushes and melds it in waves and storms so that it is shaped and smoothed into a sea gem, eventually returned to wreathe the shore. Nobody at the time could have realised this as the start of lifelong commitment for Shirley. It was births of her older sisters’ children.

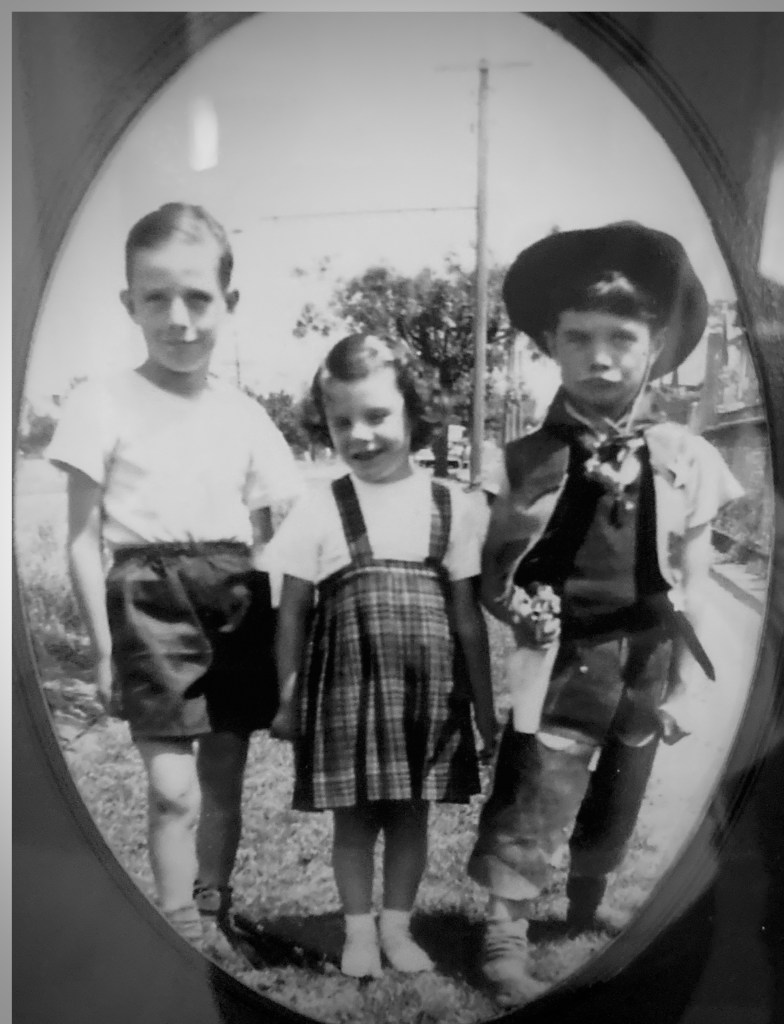

Babies were something of a mystery to Shirley, being the baby herself for so long, and when her sister Lorna gave birth to the first grandson and nephew Jeffrey, the whole family were immediately besotted by the arrival of a boy in the family after all the years of girls. He was a happy, chubby baby and he crawled cheerfully around the cold hallway of Griffith Street bringing simple joy and laughter. He was quickly followed by another boy, David – somewhat less quiet and placid, with intense eyes and dark hair, who seemed to be in his own world a lot of the time.

Lorna and George lived in George’s parent’s house in West Coburg and Shirley visited them every Saturday to dote upon her nephews, knitting them baby jackets and jumpers. When Lorna came to Richmond, Shirley would take the little boys out into the garden to visit the duck and to poke twigs through the chook pen enclosure. They were a delight. Jeffrey grew into a bonny, fat toddler who giggled every time Shirley sang to him, and David wandered around getting into mischief before anyone realised. She decided boys were much easier and happier than girls, and she set her heart there and then on having three boys of her own when she married. In 1945, a tiny girl joined the boys – Christine. She was regaled in the most elaborate layettes and her hair always trimmed with curls and bows – never leaving the house looking anything less than a baby bouffant princess. The boy’s shorts and jumpers started to take on something of an outgrown shabby appearance, and Shirley felt a little sorry for their relegation to consorts for their royal sister. She made even greater efforts to make a fuss of them when she saw the boys as a result.

So, through a haze of working at Optical Prescriptions in Collins Street during the day; avoiding going home to Griffith Street at night where Eileen and Bill were causing heartbreak and chaos; knitting socks for the war effort; spending time with Lorna’s children and at the Milton house – and missing Fred; 1944 and 1945 drifted slowly by. Parts of the world that Shirley could have barely imagined before the war became familiar now, and when battles Fred was involved with were in the papers it was a topic of great conversation, although Kate was someone to steer clear of in that case. She became somewhat hysterical at the mention of skirmishes HMAS Shropshire was involved in, and it was better to avoid her when details of naval battles made the news.

Each month or so, a letter would arrive from Fred. Sometimes there would be two in the space of a few days, and the arrival of Fred’s letters caused a huge range of feelings for Shirley. His neat florid script was impressive compared to Shirley’s own basic scrawl, and he wrote wonderful descriptions of some of the places they visited whilst being careful not to let on any ‘war secrets’. He shyly expressed to Shirley how much he missed her and looked forward to beating the Japs out of the Pacific so he could return home again in due course. There wasn’t much he could tell her about what was happening in the real world of naval battles, but he was always positive about the outcome of the operations, and that the Japs would soon be defeated and driven out. Fred wrote well and sometimes his descriptions of the faraway places that seemed so unimaginable to Shirley made her feel as if she was there. She felt rather inadequate when she wrote back rambling on about the local lads and lasses living their uncomplicated lives back in Richmond. It all sounded so boring and unreal.

Some of the ugly dramas that were unfolding in her own personal world as Eileen and Bill both tried to outdrink each other were her ‘war’ stories, but she kept them well hidden from everyone. They were shameful family secrets and ones she avoided, if possible, by spending every weekend with Thelma at the Milton’s house. She barely spoke of it to anyone, even her closest friends. She grew increasingly resentful of Eileen, but Bill became a glowering presence in the home that Shirley could not bear. Luckily, or unluckily for them all, after he got paid on Thursday, he would disappear until Monday night when he would return hungry, broke, and sober until Thursday’s wages/drinking and gambling money appeared at lunchtime on the job. If it weren’t for her mum and dad, her sister and Bill would have been homeless. Eileen’s increasingly disgraceful, drunken episodes filled Shirley with disgust and heart wrenching pity at the same time. She had witnessed the way Bill treated her sister, and the muffled beatings she had heard through the paper-thin walls of the Griffith Street house, were reason enough for Eileen’s growing obsession with grog. Yet the abject sight of her drunken sister appalled her.

The beginning of 1945 saw the birth of Shirley’s third nephew, this time to Eileen and Bill. Blue-eyed and blonde, bubbling with love and excitement when anyone passed his line of sight; Terence was a delight. Eileen managed to be a loving mother and for quite a long stint Shirley did not see her drunk. Bill was proud, and for a while he came home at a respectable time from the pub and did not disappear over the weekends quite as often. However, as the bonny wee boy grew and began to crawl around the house creating havoc, Bill once again disappeared, and the drinking and fighting recommenced. May felt heart achingly sorry for little Terry, and wrote notes apologising to him on the back of photos that she kept of him and his brother until she died. Inevitably, upon returning home from work, Shirley would find him in the sole care of her harrowed mother who was endeavouring to get tea ready in between holding the fractious child who was already needing his bedtime. Both Bill and Eileen would be nowhere to be found. Eileen, at least, would return from the hotel just after six most of the time, often in a state of drunken disarray, and Shirley’s mother would receive her with a stony silence that made the evening meal ritual more harrowing than it had ever been. On the worst nights, she would sway sickeningly to the table where she struggled to pick up the cutlery to bring the food to her mouth. So drunk was she one night that she passed out and fell face first into her corned beef and mashed potato. May screamed at her and she stirred. Arthur and May dragged her like a sack into her room. Terry started crying and Shirley tried to pacify him with a piece of bread and honey.

More things happened in the house then – she tried to frantically to forget them whenever she walked down the front steps and down the street. Her father buried himself even further into his library of literary giants and port wine; May’s trips to Tasmania became more and more urgently organised and longer in duration, and Shirley found any excuse to be out most nights of the week, so she did not have to think about what was happening or about to happen in this descent into alcoholic madness that was lived in Griffith Street every day. When Shirley did return home from work, Terry would often be wandering snotty nosed around the house, or the cold garden in his sodden nappy. If Eileen was there, she was asleep in the spare room, snoring soporifically. Finding some warm clothes, Shirley changed him, gave him milk, and sang him songs, while she peeled the potatoes for tea. That little boy had the bluest eyes, below sweet, sandy curls. The eyes of a Winter stream. He would not leave Shirley’s side while she put on the tea. Not until Arthur came through the door and tickled him before sitting down to eat. At some vague point of the evening, his mother would appear staggering to the table, then perhaps Bill his father may trudge down the hallway during dinner, if it was the night before pay day. By then however, Terry was often asleep in Shirley’s room at the foot of her bed, warm and breathing like a cat. He would wake her up in the morning and she would leave him with jam toast and milk before she had to hurry out the door to catch the tram to the city for work. Shirley would pinch the feet of her unconscious sister before she left, hoping to rouse her into motherly attendance before she had to leave Terry in the fireless house for the morning. She swallowed and bravely closed the front door. Her mother’s return from Tasmania could not come too soon.

At least during the day Eileen didn’t drink as much so there was someone to care for Terry. The poor little boy did not choose to be born into this. But nothing anyone could do made up for the beer running through his parents’ veins.

Soon enough, Terry was followed by a dark-haired, miserable baby – Anthony, and Shirley became adept at being able to sleep through a screaming infant. Without the help of May and of Shirley when she was home, those boys would have had little chance for a normal life. By the time Tony was walking, Eileen had sunk into a cycle of drinking that seemed to Shirley designed to beat Bill at his own game.

Shirley felt ashamed of her sister. Men – well everywhere she looked and nearly every father she knew – drank. They all got full every night. It was just life in Richmond. But the shame around women who drank and got drunk in public was against everything that the nuns and society had ever taught her. It was a terrible humiliation and embarrassment. Shirley hated Bill for what he had done to Eileen, and she hated Eileen for what she had done to herself, her boys, and to her mother and Shirley. She would never forgive her.

Chapter 18

Waiting for Fred

During Fred’s naval service, his younger sister Thelma and Shirley forged a solid friendship over their shared years in the Children of Mary and the thriving social life of the Richmond catholic community, and this grew even stronger after the departure of Fred to the war. Shirley wasn’t interested in dating or hanging around the other boys like Lorna was, so even though she and Lorna still shared their usual nights of dancing, movies and choir nights, Shirley spent a lot of time with Thelma and at the Milton’s home. The girls both loved dancing, and most Saturday nights they would head to the St Kilda Town hall where a fancy dance would attract a huge crowd every weekend, and they could dance all night to a big band for a shilling.

At the end of the dance on Saturday night, it was easier just to stay at the Milton’s because Shirley always had to walk Thelma home to Clark Street first, walking past her own street by a good mile or so to deliver her home. Thelma was too nervous to walk herself home alone, although it didn’t seem to occur to her to wonder what happened to Shirley once she dropped her off and headed back into the night to Griffith Street on her own. Back at home, Eileen and Bill had moved in and Eileen was pregnant. It was bedlam most nights at home, and the Milton’s lodging offered peace, calm, and half a shared double bed with Thelma in contrast to her own tiny box of a bedroom and the misery of lives deconstructing under the pall of beer and whisky. Without Fred around to remind Mrs Milton that Shirley was in danger of snatching him away, Kate treated Shirley quite kindly. Whilst no one in Richmond’s kitchen was laid on with endless supplies of food, there was a much higher chance of getting fed some morning and afternoon tea at Clark St, and Shirley learned a few cake and scone making recipes emanating from the tiny kitchen.

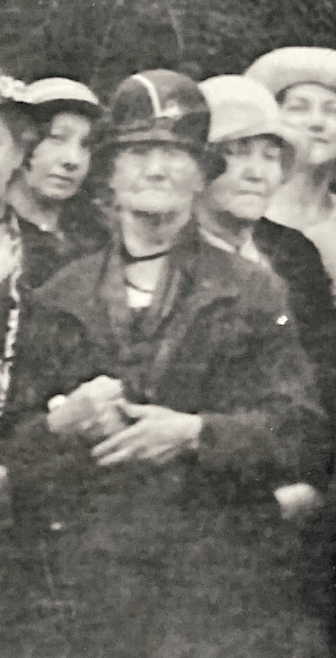

Sam, Kate and young Fred and Thelma in their horse and jinker on the farm at Silvan

Thelma’s terror of walking around the night streets of Richmond were something of a mystery to Shirley, but she learned later on that they had a very organic inception. Thelma had grown up tightly wound up in her own mother’s anxieties, rightly or wrongly springing from Kate’s experience of hard bush life bearing babies and fretting about how to feed her four children each day during a depression, all the while keeping the wolves of poverty and (more unsuccessfully) coldblooded banks at bay.

Fred with Thelma in the pram 1927

Some eight years ago back on the farm in Silvan, when Fred was around ten years old and Thelma only eighteen months behind, Kate fell pregnant with her fifth child. Life had never managed to progress past spartan sufficiency up in the mountain where they moved when Fred was two, and the family struggled to survive and feed the children they did have after paying for the running of the farm and the loan they had taken out to purchase the property. There was little time to think about anything other than the cooking, washing, cleaning and farm work that was needing to be done, so there was little time to even register the existence of a looming new addition to mouths to feed. However, some thirty weeks into the pregnancy, Kate woke up with severe contractions and before help could be called, a tiny baby boy was born pale and unmoving. Sam took the little one the next day as soon as it got light – before the children woke – and buried him under a large tree in a grove deep enough to make sure that no one knew he was there, hoping somehow in doing so life could return to normal for his wife as soon as possible.

Fred and Thelma centre front at smoko time in the Strawberry fields at Silvan

Later that morning Kate did stop crying, but the next day when Sam returned from his work in the fields, she had stopped speaking. Sam tried as much as he could to keep the children out of her way for the next week or two, hoping that with rest she would recover. He made simple meals for everyone with the assistance of Fred and Thelma, and they helped him to get the younger ones dressed and fed before they left for school. However, when he returned home for lunch each day, he would inevitably find Kate sitting by the fire staring at the wall in the same seat and position as she had been when he and the children had left four hours earlier. She would not respond to conversation and barely ate or drunk anything. Her eyes stared fixated into the middle distance and it was as if there were no one in the room, even when it was filled with the four children and himself.

After two weeks of this, he called in on his sister-in-law Grace who lived nearby and asked her to send word to the Melbourne chapter of the family that Kate was not at all well after the loss of her pregnancy, and that she needed assistance. Bonnie arrived a few days later, distressed to find Kate barely responsive, rod thin and dishevelled. After cleaning up the cottage and putting on a stew for the family, Sam drove Bonnie and his wife to the train station back Melbourne, where Kate spent the next two months being nursed back to health. Thelma, Fred and Sam kept the family going in the meantime and they all went on with life as much as they could without their mum to keep things going. Her children, while missing her terribly, were both confused and relieved not to have to tiptoe around her stricken form sitting in front of the fire from breakfast time until bedtime every day.

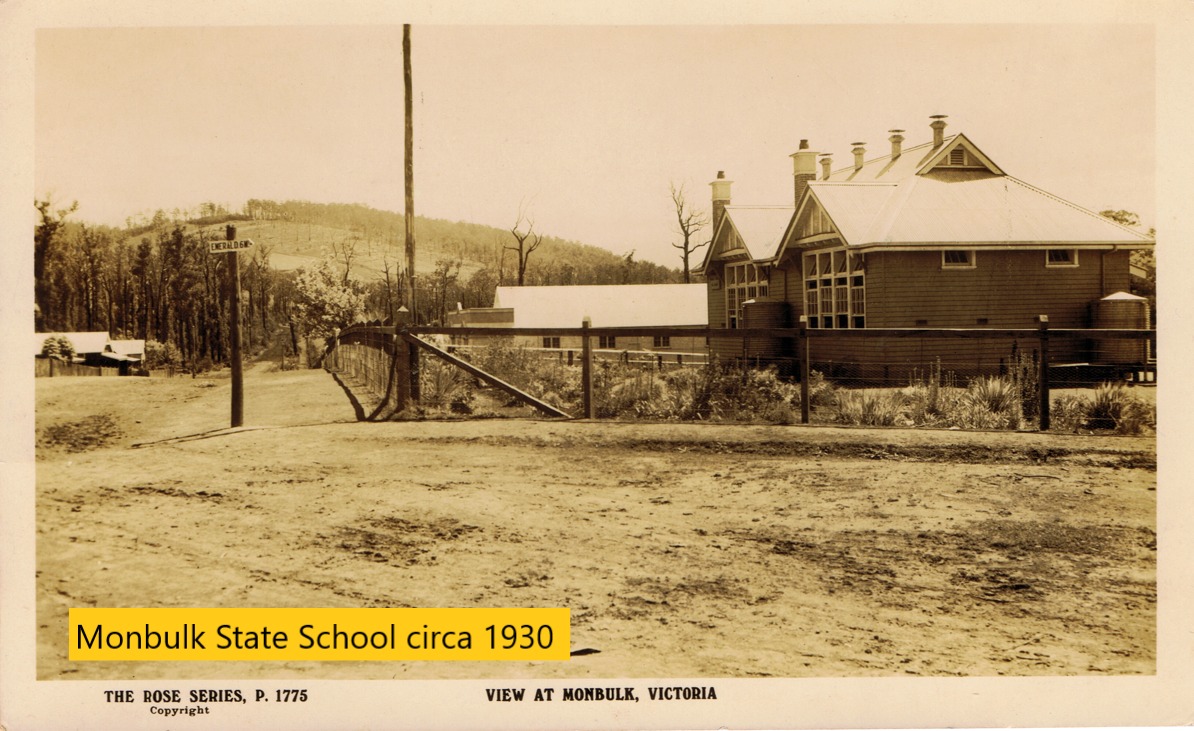

The primary school the Milton children walked five miles to every morning in Monbulk

Eventually, Kate recovered and returned to Silvan and life seemed to her brood to go back to normal. Some two years later however, when they had almost paid off the block, the depression deepened so much that the laden cart full of fresh berries would leave the farm late at night and return the next day at dusk with barely a case sold. It quickly became impossible to keep up the loan repayments, and the bank began foreclosure, forcing Sam and his family into Monbulk where he worked for the next few years at whatever jobs he could find to put food on the table. Fred and Thelma left primary school and started commuting down to Swinburne College to complete Grade Seven and Eight, with Sam eventually finding a job through family as a delivery man for the Loy’s Lemonade company down in the big smoke. In 1939 the family moved to Richmond to start a new life, abandoning their shattered dreams of rural prosperity with great relief.

Ever since those hard years in Silvan and her breakdown, Kate seemed to live on high alert in life. To Kate, the world was a savage place, to be feared and fought and kept at bay by strict adherence and attention to safety and thrifty housekeeping. Thelma, as her oldest daughter, was instructed to never trust life and its grimy streets. It threatened ruin, danger and overwhelm at every turn. The towns, cities and establishments of this world were to be dreaded, the battle for shillings and bread a ceaseless threat to one’s personal safety, and the importance of a secure wage trumping all personal needs or desires.

Monbulk Primary School Fred centre front, Thelma fifth from left row three

World War II and the Australian Navy had now introduced a life-threatening element into the safety net Kate had tried to construct around her family completely outside her control, and her anxiety became a nagging ghost that no number of saved shillings on the fridge could allay.

When Sam was sent away to work for the civilian war effort, and her cherished oldest son in the Navy was at risk of being killed at war in Asia, Kate’s forbearance in accepting such a devastating alteration to her family life soon crumbled. Not long after Fred left for his naval service, Kate was unable to get out of bed one day and when Thelma called the doctor he arrived to a screaming reception in the front bedroom. Kate lay twisting the sheets in her hand and crying uncontrollably. Dr Pivott prescribed some brandy and milk of magnesium and wrote later that day to the Australian Home Defence Forces Directorate instructing them to send Mr Samuel Milton directly home to his family as there was no one to care for the two younger children while the mother was in such an unfit state. Sam returned home as quickly as he could, happy to be released from the hard physical labour, and deeply concerned that his wife appeared to be struggling again so greatly with her nerves.

Sam always had a calming effect on the house. His simple yet kind conversation helped everyone relax, and Shirley was relieved when Mr Milton was home whenever she arrived. He had a soft, warm smile and was a deft hand at carving a modest lamb roast into graceful portions that lasted for three meals. With Sam safely back in Richmond and recommencing his delivery job for Loy’s Lemonade, Kate gradually regained her equilibrium and the family moved on as best they could, happy that at least their father was there now to lend a helping hand and a soothing smile every day.

Chapter 17

Wanda Hurley, dating and enlisting

Towards the end of her first year of work, Shirley was invited to the social event of the year – Wanda Hurley’s 16th birthday party! Wanda Hurley was about as close to a beguiling, beauty goddess as it was possible for a young girl in Richmond in 1942 to be, and there wasn’t anyone who held the boy’s attention quite like her. In fact, anyone who was anyone from St James and St Ignatius was invited – not to mention the Children of Mary and the footy, cricket and water polo teams; some of them already budding soldiers and sailors lining up to do their bit for the war effort. The pre-party excitement was far reaching throughout the young Richmond community, and not many conversations with the boys at the corner of Highett Street and Griffith Street involved talk of anything else in the two weeks leading up to the big night.

Wanda seemed to emanate a mystery and glamour that was more than just her good looks. It was true that her hair was a flaxen white blonde; her satin lips curled up slightly where her dimples caressed the bottom of porcelain cheek bones; her large, pure-blue eyes were surrounded by an envy of black lashes, and her baby pink skin glowed with a halcyon freshness that emulated the movie stars who only dwelt ghostily on the screens at the ‘cin’. But even more fascinating for her admirers was that her parents lived in a posh part of Richmond where the houses dwelt further back into the wide, rose lined front yards, and there was even room for a shiny car in the driveway. She held a social power of privilege and the implied, mysterious luxury of wealth that was unheard of in the slums of Richmond, adding all the more allure and fascination to her larger than life aura. All the boys were sweet on Wanda, and whilst Lorna and Shirley, along with most of the other girls, secretly resented her, they were always jolly and polite around her in case they were excluded from whatever events she was central to, because all the handsomest boys shadowed Wanda Hurley wherever she went.

Lenny Voight was one of the jocular, local boys who had wooed Shirley at the ’Learn to dance’ and she found him great fun as he always made her laugh. He was a handsome young boy, easy to talk to, and a great footballer to boot. After asking Shirley to go to Wanda’s party with him, he picked her up from Griffith Street, talking excitedly as they walked along the streets of Richmond trying to keep warm in the Wintry air. Disastrously for Lenny however, he had recently taken up cigarette smoking with a vengeance, smoking at least three cigarettes on their way to the party and continuing almost non-stop once they were there. When the music started, they danced, but his breath nearly made Shirley sick. She couldn’t stand it when he leant over to talk to her and had to pull away from the stench of it. Shirley made her way to the other side of the room to speak to Lorna and her other girlfriends where she decided to keep her distance the rest of the night. It was then that she noticed Fred Milton glancing shyly at her. His dark ginger waves and his bright blue eyes were what impressed all the girls. Even though he was shy, he talked easily enough with the other boys there, and there was something kind and soft about his face that made Shirley feel soft inside too. It was effortless to ask him to join the throng on the dance floor. They spent the rest of the night dancing together; Fred had good rhythm and they swung around Wanda’s lounge-room with all the other couples in a warm haze. When they had a break for a drink, they had a great long chat, more than they ever had before. Fred loved the way Shirley laughed so vivaciously, and it made him feel at ease and comfortable around her. As for Shirley, Fred was a real good looker. He was shy, but when you got talking to him, he had plenty to say. They got along well and could talk about anything. He opened up around her.

At the end of the night, Shirley left Wanda Hurley’s party with Fred Milton, leaving Lenny Voight to chuff his own way home alone. Fred didn’t smoke and he was much nicer company anyway. He walked her home through the wintry streets to Griffith Street. As they neared the corner of Bridge Street, Shirley chirping away about the antics at the party, Fred passed his hand lightly across hers. They parted outside number sixteen and in his agonisingly shy way he asked her out the next week on Tuesday night. After that the only weeks they ever spent apart were the ones when he was at war. But all of that was still years away. There were plenty of dances to enjoy before then.

Shirley and Fred soon settled into a contented existence together going to the ‘Learn to Dance’ on a Sunday, and on any fine days there would be a picnic in the park or at the South Melbourne beach. Extra excitement came along when there was a dance at the St Ignatius, or at the St Kilda or Richmond Town Halls. Fred would occasionally come over for tea at Griffith Street and got along well with Arthur and May who thought he seemed like a neat, intelligent young man, and after a month or so, Shirley was invited home to meet Fred’s parents. Mrs Milton was a thinly polite, impressively checked-aproned matriarch. She was somewhat intimidating, and rarely included Shirley in any conversation. On the other hand, Mr Milton was warm-eyed and kindly, and always asked Shirley about how her week had been. Shirley was great friends with Thelma so there was always plenty to talk about with her at least. The younger two, Raymond and Joan, were chirpy enough, and they all appeared able to be quite benevolent to each other around the dinner table as conversation was allowed, which was always thrilling for Shirley to observe.

Life settled into an exciting new phase where Shirley escaped the drudgery of Griffith St and the inebriated yelling and fighting (or worse – silences) by going to work, spending time with Lorna or on dates with Fred. The war began to rage in the distant world around them but still seemed very far away. Rations, sock knitting, and war service became common everyday activity and terms. In many ways, her life opened up as a young woman during the war years.

Fred and Shirley became a regular couple around the circuit of dances and picnics. Fred wasn’t one for the movies, so when Shirley did go it was usually with Lorna and some of the other girls from the Children of Mary. She loved just sitting and talking with him and they could talk for hours about all the characters at work and at home, and the footy, even though he barracked for Melbourne and not Richmond. As for Fred, he marvelled at the way he didn’t feel shy or awkward around Shirley. When he was with her, he didn’t feel worried about anything he said, or how he acted. What limited attempts he had made at talking to girls prior to her had been agonising. Shirley just made him relax and come alive. She was always interested in what he had to say and how his day had been. All his little stories interested her, and he was able to share with her the feelings that he went through as a telegraph messenger when he had to deliver notifications to the families of those young men who had lost their lives in the war overseas. Merely a boy himself, he had no idea what he was supposed to do, even though the instructions he received in his position was to wait until the recipient had read the telegram to see if they wished to make a reply. He would hover in mortification as he was forced to watch the mother of a young boy scream in disbelief and shock at the news that her son was lost to the war. It was a trauma he would remember his whole life. His parents listened to his recounts if he wished to tell them, but when he realised that he would be joining these young boys himself soon, he preferred not to tell such stories, especially to his mother. Shirley would listen though and seem to be able to understand what it felt like to look into the eyes of those parents and hear the words of wracked grief that first escaped their mouths.

One day at the beginning of 1944 when they had been going out about 18 months, Fred suddenly announced that he was going to sign up for the Navy on his eighteenth birthday in the May. They were walking to his parent’s place for dinner when he blurted it out. Shirley had not asked him if he was interested in going to war for fear of what he might say, and Fred had not volunteered any hints about his feelings on the matter. As long as they talked about ‘white chooks’, there was nothing to worry about. However, the war was another story altogether. Suddenly her world seemed to collapse inwards and all the ways in which she had coped with the world, in its small and simple way, seemed to swirl away from her now. Her experiences had expanded outwards from the misery and quietude of Griffith St ever since she reached the days of finishing school and moving into work, and now Shirley felt sick that Fred was going to leave for who knew how long, and her world would be diminished once again back into the silence of the tiny kitchen behind the forbidden library.

Fred’s mother was absolutely appalled by the news of her oldest son enlisting in the war. The idea that her cherished first-born son could be exposed to any threat of death or injury and would be away from his home, with no idea when he was likely to return, seemed more than she could cope with. Sam, Fred’s father, still in his early forties, had been drafted to complete civil labouring service for he still had much to contribute according to the Australian Government. He’d started commuting up to Albury/Wodonga for two weeks at a time in 1943 to help build an airstrip. Now that Fred had announced he would be leaving the family home to complete his Naval training and she would be left to run the family on her own with only the teenage Thelma to help her and Raymond and Joan still children, it was all too much for Kate to bear.

This new change in the family’s dynamics, on top of her having to deal with her treasured son now being involved with a girl who seemed nowhere near good enough for him, threw Kate back into a very difficult place. Shirley tried her hardest to be a friendly, polite and acceptable girlfriend to Fred, and a happy friend to Thelma, but neither of these recommendations meant much to Kate. Her son was destined for someone much better than Shirley. In fact, he was too young to be throwing away his life and affections on any of the local girls at present, and she felt confident that the war would sort all this nonsense out anyway, so there shouldn’t be too much to worry about.

In May 1944 Fred enlisted in the Australian Navy, and with the war being on a messy but promisingly victorious pathway in the Pacific, the Australian Navy didn’t waste its time getting the young lads down to Flinders Naval Academy for their accelerated training, and after a couple of months it was time for a farewell dinner and one last walk around the Richmond Gardens hand in hand to say goodbye.

Shirley was reeling as most certainly it would be several years before she saw Fred again at best. In their too brief courtship, they had discovered a warm and wonderful togetherness where they could talk endlessly, laughing at the characters around them in the colourfully, grubby world of Richmond. Fred had bought her much happiness and hope for the future, amid the woes of Griffiths Street’s unfolding tragedies.

On his last weekend as a civilian, they walked home to Shirley’s after a dinner with the Milton’s and said goodbye with great sadness. It hardly seemed real, but it would still be some time before Fred’s last visit home. They both knew that things were changing between them for a long time, and though they couldn’t talk about what that meant, they clung to each other for a long time feeling bewildered by all the emotions that were swirling around them. It all seemed bigger than the two of them anyway, and out of their hands. Luckily, the next few months afforded them a few brief opportunities to catch up and spend a few, last precious moments together.

When the final ship out date arrived, Sam came back from Albury for the weekend and Kate cooked up the sort of feast that one was able to manage in the middle of rationing, and they had a jolly party. Her sisters Bonnie, Mary and Gracie came along with their families, and old Dan, her father, wasn’t to be left out either. Fred was his oldest grandson after all. Regrettably Dan always managed to spoil any dinner he turned up to, but all things considered he was well behaved this time. Kate’s sisters were in high spirits and only needed one or two shandies before they started singing ‘Knees up Mother Brown’ and ‘Danny Boy’ jigging around lifting their skirts lightly and showing their legs above their knees, much to the hilarity of the rest of the party. Rationing was probably curtailing Dan’s ingestion of sherry, so he didn’t berate the company as caustically as he usually did.

The next day Fred’s train left for Spencer Street at 0900 to join the HMAS Shropshire in Sydney, and while there were plenty of tears as the train pulled out, Kate chose to stand at another point on the platform near Shirley and even when Shirley attempted to acknowledge her, she seemed to look through her like a ghost. Kate was in shock, pale faced and bereft that day. It would be almost 18 months before either of them would see Fred again. It was the 4th of July 1944.

Chapter 16

Grandmothers and other battles

‘Stand your ground!’

During Shirley’s studies at the Daycomb School of Business, Sarah Redding (Heaney), Shirley’s grandmother and the matriarch of the Redding clan, began to fail in her health. After a visit from her doctor and discussion with family, a plan was cobbled together in which Sarah was to have a relative look in on her every day to make sure she had food for her dinner and was helped to bed. Four young girls, who were either granddaughters or nieces of Sarah were enlisted to help with the care roster, and Shirley was made to take the trip out to Carnegie to her grandmother’s house every week or so, after her day of running up and down Collin Street and puzzling over the hieroglyphics of shorthand. It was the one night of the week Shirley dreaded, but there was little to be done about it. Dutifully boarding the old red rattler out to Carnegie from the cloudy city promenades and alighting to sullen, suburban streets, she plodded up the hill to her grandmother’s little flat – the cold wind eating at her bones. As she turned the door knob, she felt a tingle of chill boredom and the tedium of her evening ahead wearing her thin before she even entered.

Sarah with her children Harold and Kathleen in the front garden of ‘Redding House’ in Benalla in earlier decades

Her grandma Sarah sat impatiently waiting in her armchair, steeped in the smell of mothballs and old paint. The flat was dull, even in the middle of Summer; the light struggling to get in the murky windows for all the ancient farm furniture from the formal sitting room that she had lugged down to Melbourne when the farm was passed on to a cousin. Shirley was immediately instructed to prepare the dinner, which always consisted of mashed potatoes, peas and some bland morsel of meat. They ate at 6.15 p.m. on the dot, and in silence, except for the persistent rattle and splutter of cars, and the horses and jinkers that ran down the road outside her door.

Sarah Heaney was an Irish-Australian, bush-born-and-bred iron woman who had miraculously outlasted a harsh farming life in the back blocks of Benalla in the late 1800s, while rearing six children. She had survived that tough, physically exhausting, mind-numbing existence by adhering to absolutes. There was a long list of them that punctuated her everyday life and they had been her mainstay as a young bush girl, an overworked farmer’s wife, and a politely loved family relic. They consisted of a list of adages such as ‘Children should be seen and not heard’, ‘The early bird catches the worm’, ‘Beggars can’t be choosers’, ‘God helps those who help themselves’, and ‘Stand your ground’ among many others. Sarah was as strait laced as they come; a lady – a monolith. It seemed to Shirley she had not changed at all for as long as she could remember, except that now she seemed a slightly smaller, shrivelled version of herself. Her face had sunken around her tooth-gapped mouth, and she slurped shamelessly on her food and drink as a result. She smelt of dusty old skin, threadbare blouses and sour perspiration.

After dinner there was a sombre stint of listening to the ABC news on the radio for an hour, and then it was time to prepare for bed. Shirley helped Sarah undress and put on her hand embroidered nightie. Her hair was a stark, shiny silver and it spent everyday ignored in a pristine bun. At night it was released like a fossilised relic from a ruin – tumbling around her shoulders in a thin, eerie veil – longer and finer now that her frame was shrinking in size. Her grandmother sat imperiously on her bed holding out the silver hand brush that spent each day sulking primly on her dressing table.

‘Stand your ground girl!’ came the order – and young Shirley would commence brushing out the silver stream of hair with large clumsy strokes until it gleamed. It was a ritual that Sarah deeply enjoyed in her own stately way. Then she was helped into bed, propped up while Shirley prepared her ‘gruel’ for supper. This consisted of some pale, insipid oats boiled in water with a little salt and sugar. Sarah slurped her way through the bowl while Shirley prepared for bed herself, sleeping on a small divan in the corner. Summer or Winter, once Sarah had finished her bowl of gruel and belched ceremoniously, the lights were turned off within a minute or two of eight o’clock, and the night was over. Well … not exactly over for Shirley, who finding sleep elusive, continued to toss and turn on the uncomfortable divan for an hour or two afterwards.

The following morning at 6 a.m the alarm clock exploded, and Shirley would be ordered out of bed to get tea and toast. After helping Sarah dress and making the bed to her satisfaction, she was tipped out of the flat into the cold, dark streets. Catching the next train at Malvern station, she would find herself at Flinders Street at 7.30, an hour before the college even opened! It was a long, cold wait loitering on the busy morning pavement, but eventually the sisters would arrive to unlock the doors, and Shirley could get in out of the cold.

After a year of typing and cleaning the toilets, Shirley was definitely looking forward to a life of independent employment. She was lucky enough at the end of the year to be offered a job at Optical Prescriptions on the Bourke Street hill, and her first pay packet was a cause of great celebration for her and Lorna, who had also commenced her own typing career. Even after making her contribution to the family budget, Shirley felt the power of having her own money for the first time, and thriftily planned all the important purchases she needed to make.

The war also bought a new excitement to life – at least for the first year or two. The papers were full of valiant stories of successful campaigns, and disconcertingly strange maps of foreign countries. Posters appeared on street corners and in shop windows filled with the radiant faces of women in the land army, and muscly young men striding off to do their bit. It all seemed a strange new world. A few of the boys were itching to be old enough to get involved in the war, and were counting down the days until their 18th birthday. There were still plenty of boys who were in essential services and were required to stay put, so thankfully there weren’t too many impositions on the social life in Richmond.

On occasions throughout Shirley’s life, May’s relatives from Tasmania had ventured up to the mainland for a visit. She was their source of accommodation in Melbourne, and Richmond was a popular spot from which to experience the hubbub of a big city. South Franklin was about as different from the backstreets of Richmond as two places can be, and it would often be Shirley’s job to help the country folk around the busy streets of the city giving advice on either walking or taking a tram to where they needed to go, without being mowed down by vehicular transport.

Phillip Oakford, Shirley’s cousin from South Franklin, had enlisted in the Navy, and while he was waiting for his start at Flinders, and during his leave breaks, he would come and stay in Griffith Street. Shirley had met him and liked him as a little girl when he was a teenager in Franklin, and they got along well now too. He broke up the dynamics of the household, and there was someone to yarn to and joke with when he was on furlough. In 1941, his commission was about to start, and he discovered with great excitement that he was being posted to the HMAS Sydney. His brother, Les, had just completed a tour to Europe and Alexandria, including some famous victories at Calabria that made the front page of the papers. It was the prestigious pride of Australia’s fleet, and there were celebrations at Griffith Street the night before he left for service involving a special treat of roast meat and gravy, pudding, beer and rum. Two brothers could not be aboard the same warship, so Les came off the light cruiser to allow Phillip to go onboard, feeling quite chagrined to lose his place on this famous arsenal in the war.

They said goodbye the next morning at the train station. Phillip was wordlessly excited as he farewelled Shirley and May. Promising to write, he disappeared into the buoyant mass of sailors and soldiers boarding the train. Shirley felt a strange jealousy of the glamour and adventure of it all.

In the space of a month, Phillip was lost along with all 644 crew of HMAS Sydney. She sank alone and afire after a thirty minute battle with the German auxiliary cruiser Kormorant on evening of the 19th of November 1941, near Dirk Hartog Island off North-Western Australia. It took over four days for a search and rescue mission to be launched. The telegram arrived from May’s sister in Franklin a few days later, while Shirley was at work. When she returned home to the news, her mother’s bedroom door was locked. Shirley did not see her for a week.

The disastrous circumstances of the sinking of the Sydney was shrouded in secrecy for years. The rather unassuming news report above appeared on page seven of the Melbourne Age newspaper a full week after the Australian government knew of the loss. It took until the 1980’s for proper research of the tragic incident to be released to the Australian public. The wreck was finally found some 70 years later.

Chapter 15

Nephews, Typewriters and Daycomb Shorthand

Shirley’s mother May with her grandson

Shirley had no real understanding or knowledge about babies. Her world was full of older relatives, and she was the youngest daughter of a youngest daughter. Her father’s brothers had a couple of stuck-up young sons who were a few years older than her, and that was the extent of her experience of family children. So, when her sister Lorna gave birth to Jeffrey in 1942, she was unprepared for the aching love that filled her heart when she saw the little squirming package in her sister’s arms. Her mother was quite beside herself at the birth of not only her first grandchild, but a boy as well. Shirley had never seen her mother so dewy eyed and disarmed. Jeffrey was such a beautiful little baby boy. Shirley spent hours playing with him and holding him whenever she could prise him out of Lorna or her mother’s arms.

Grade 8 was ending, and plans were well in hand for most with moving on to jobs in the local factories, shops, trades, family businesses or public service. Sister Maxentia had been the titanic matriarch of St Jimmies’ who, with a firm, kindly and perceptive mentorship, took on the bristling young crowds in Grade 7 and 8s, preparing the majority of them for the world of work. Over the two years that she worked with these swiftly maturing, commonly impoverished catholic teenagers (before that term was generic) Sr Maxentia had doggedly yet calmly informed herself of each of their personal situations, inclusive of innate talents and intractable limitations, and been instrumental in fostering their secure ‘passover’ into earning their keep. She heard and knew (because in that community nothing was secret) the many tales, whispered or free-spoken, that each of these young people confronted outside her school walls; and it was her yearly quest to ensure that, at the very least, they were leaving school with the guarantee of secure pay at the end of each week to ensure they could look after themselves no matter what the swirling situations around their daily living arrangements threw at them. She wielded substantial influence with a range of the local catholic businesses, many of whom were former clients of hers, leveraging irrefutable pressure when in need of placing a child who was yet to find their own employment. To Shirley though, she became a loving and affirming touchstone. A kind and motherly stalwart. Shirley would miss her enormously, yet she was very relieved to be able to escape the agony that was her school studies, where she had often felt dull and inadequate, and beyond all of that, bored! And with no less than the exciting prospect of growing up and having her own money beckoning to her, Shirley was a swathe of excited emotions.

May had organised, somehow, with the Daycomb sisters, who owned their own newly established college in Little Collins Street, for Shirley to commence business studies including typewriting and Daycomb shorthand skills for twelve months. There was little chance of her mother finding any money for Shirley to attend this prestigious business college, but after May made her own personal persuasive pitch, Clara Daycomb offered a subsidy to Shirley with the proviso that she took the job of being pulled out of class to run messages whenever they needed someone to do an errand.

Thus, Shirley was introduced to the glamourous world of typewriters and shorthand. The teachers at the school were thin, prim, and very self-important; all ruled by the garrulous and cheery Clara and the dour, imposing, intimidating Beatrice. They scurried around the gloomy corridors and bustled the girls into dinghy classrooms where they were taught the importance of being an army of well-behaved, easily overlooked typists and receptionists, who were marking time until they could stop work, get married and spend the rest of their days being well-behaved and easily ignored wives and mothers.

Daycomb Business School,

The Presgrave Building, 279 Lt Collins St, Melbourne

The smell, and smooth pedals of the typewriters and the tapping of their impressive metallic keys seemed redolent of such a romantic and official atmosphere. Shirley, however, wasn’t a naturally fast typist, and felt frustrated with the speed and clumsiness of her hands, but she worked very hard and diligently when given the chance, eventually cracking the magic rate of 35 words per minute – the lowest benchmark for graduating girls. Daycomb Shorthand was another challenge altogether.

With the many interruptions occasioned by her trips up and down Little Collins Street to the other connections of Daycomb Shorthand in the business community, there were important chunks of shorthand classes that were lost completely, and catching up presented an almost impossible challenge for Shirley. No matter how much homework she tried to do in the her cramped little room, it always looked like Chinese to her.

In her class there were a fun bunch of girls that Shirley eventually teamed up with, and they would hang around down at Healey’s cafeteria where they would sometimes have the money for a milkshake and a Chester Slice. Her first days at the college were lonely ones however, because it was the first time Shirley and Lorna had not been together sharing each of their school days chugging through the boring grammar books, and trying to keep their many flirtations with the boys from St Jimmy’s under wraps.

Lorna went to a competing business school where she learned Pitman shorthand instead. To compensate, they began to meet on the corner of Highett and Griffith Streets at the end of each of their business college days to catch up on the exciting new events, people and skills that had come their way that day. They also organised to enrol in a sewing course together at William Angliss College on a Tuesday night, starting out diligently enough in the program learning the basics of dressmaking. As the year wore on however, and the streets of Richmond became icy and bitter wind tunnels, the girls would shiver as they set off down Bridge Road together to the tram stop into the city, passing the ‘Cin’ on the way. Outside, under the bright lights, groups of their friends would be hanging about waiting for the session to begin for the most recent movie. With the foyer looking so tempting and so warm, and much more fun than the unwieldy sewing machines they were otherwise going to be ‘watching’, there were a few of the sewing classes that came off second best some nights, and Lorna was never to go on to develop a great knack for running up quick, simple, cheap, and cheerful costumes in her future – no matter how many children she had who needed them! Shirley on the other hand remained more of the driving force in support of their sewing course, and she actually managed to get them on the tram safe and sound most of the time, sewing kit underarm – with the ‘Cin’ and the tribe of boys outside, disappearing disconsolately behind them.

Chapter 13

Shirley first row centre, Lorna next to her. Thelma second row rear left

The War comes to Richmond

Shirley plodded along at school, far from the perfect pupil, but diligent enough when the nuns were looking, and up for an antic or two when they weren’t. At the age of 12, the war in Europe was declared and the talk in the streets on a warm night as Summer approached revolved around the evils of Hitler and the Nazis; whose son, nephew or brother was enlisting and in what service. In the shops when Shirley fetched the messages for her mother, or tobacco for her father, the talk was that the Huns were at it again, and it was time to teach them a lesson for good. Shirley didn’t take too much notice. Inside the world of St Jimmies, and in the familiar blocks of Richmond’s community, life held much more thrilling and engrossing news items and ‘headlines’.

When she and Lorna reached Grade 8, their friendship network was large and sprawling. They were a magnetic duo, always in the middle of a group of hooting boys and girls at school, or after school on street corners where groups would congregate chatting to passing friends and the telegram boys, in between school and being called home for dinner.

Another exciting development that starting Grade 8 afforded the girls was the chance to join the ‘Children of Mary’. This most sacred and glamourous group imbued its members with a nun-like aura without any of the restrictions upon looking pretty and flirting with the opposite sex. It involved sitting together at Mass and singing the hymns that accompanied the ceremony. It also embraced the sacred flaunting of a soft, voluminous, knee length blue cape tied daintily at the neck, with hair decorated by a delicate lace mantilla. The angelic costume was the real attraction of the whole proceedings; the sky-blue cloak made one feel like a high priestess; creating a vision of holiness as it swept majestically around them as they walked chit-chatting down the tattered streets of Richmond towards the church – the white lace perched on their curls lending an almost matrimonial air to the outfit. In fact, it would be worn by some of the girls over their wedding dress on their wedding day years later. Wearing The Children of Mary outfit was a serious and solemn business.

When they began their first rehearsal after the Summer, there were a few new girls in the legion; one of them was a new face in Richmond sporting a shy smile and luminous curly dark red hair. Lorna and Shirley noticed her straight away sitting with Mary Scully and introduced themselves during the break in singing. Lorna observed brightly, ‘I love the colour of your hair. Shirley and I think it is so pretty. What’s your name?’

The young girl bowed her head and smiled slightly, wringing her hands against her knees and looking wide eyed, terrified and friendly at the same time.

‘My name is Thelma. We just moved down to Richmond a few weeks back. Dad had a farm in Silvan, but he had to give it up.’

‘Oh, how d’ya like Richmond so far? A lot of people don’t like to mention that they live here. But we have a great time with our bunch of ‘china plates’. You hafta stay on for the Learn to Dance after this. It’s all Victor Sylvester tunes… and after Sunday morning Mass we have a morning tea and everyone brings a plate. The girls are a lot of fun!’ enthused Lorna reassuringly.

Thelma laughed shyly as Shirley and Lorna were joined by Kathleen Martin, Joycie Goodwin and others. They entertained Thelma with stories and jokes before rehearsals. All the girls were extremely excited to be old enough to join the Children of Mary for many reasons Firstly, because it was something to do on a Thursday night, secondly, it seemed such a devoutly mysterious thing to do, thirdly, the boys always took a second look as you swept down the street past them on the way to rehearsal; finally and most importantly, it was followed by the weekly ‘Learn to Dance’. The hall’s rafters transformed from reverberating holy arias to echoing a buzzing, bright-faced ballroom where enormously popular tunes by Victor Sylvester such as ‘I’ve got my eyes on you’ and ‘You’re dancing on my heart’ helped choreograph the eager polished shoes and cheery slightly worn heels of the excited attendees. And it only cost a threepence to cover the electricity!