Grandmothers and other battles

‘Stand your ground!’

During Shirley’s studies at the Daycomb School of Business, Sarah Redding (Heaney), Shirley’s grandmother and the matriarch of the Redding clan, began to fail in her health. After a visit from her doctor and discussion with family, a plan was cobbled together in which Sarah was to have a relative look in on her every day to make sure she had food for her dinner and was helped to bed. Four young girls, who were either granddaughters or nieces of Sarah were enlisted to help with the care roster, and Shirley was made to take the trip out to Carnegie to her grandmother’s house every week or so, after her day of running up and down Collin Street and puzzling over the hieroglyphics of shorthand. It was the one night of the week Shirley dreaded, but there was little to be done about it. Dutifully boarding the old red rattler out to Carnegie from the cloudy city promenades and alighting to sullen, suburban streets, she plodded up the hill to her grandmother’s little flat – the cold wind eating at her bones. As she turned the door knob, she felt a tingle of chill boredom and the tedium of her evening ahead wearing her thin before she even entered.

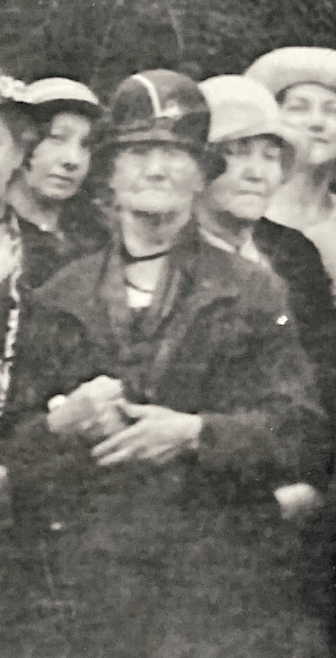

Sarah with her children Harold and Kathleen in the front garden of ‘Redding House’ in Benalla in earlier decades

Her grandma Sarah sat impatiently waiting in her armchair, steeped in the smell of mothballs and old paint. The flat was dull, even in the middle of Summer; the light struggling to get in the murky windows for all the ancient farm furniture from the formal sitting room that she had lugged down to Melbourne when the farm was passed on to a cousin. Shirley was immediately instructed to prepare the dinner, which always consisted of mashed potatoes, peas and some bland morsel of meat. They ate at 6.15 p.m. on the dot, and in silence, except for the persistent rattle and splutter of cars, and the horses and jinkers that ran down the road outside her door.

Sarah Heaney was an Irish-Australian, bush-born-and-bred iron woman who had miraculously outlasted a harsh farming life in the back blocks of Benalla in the late 1800s, while rearing six children. She had survived that tough, physically exhausting, mind-numbing existence by adhering to absolutes. There was a long list of them that punctuated her everyday life and they had been her mainstay as a young bush girl, an overworked farmer’s wife, and a politely loved family relic. They consisted of a list of adages such as ‘Children should be seen and not heard’, ‘The early bird catches the worm’, ‘Beggars can’t be choosers’, ‘God helps those who help themselves’, and ‘Stand your ground’ among many others. Sarah was as strait laced as they come; a lady – a monolith. It seemed to Shirley she had not changed at all for as long as she could remember, except that now she seemed a slightly smaller, shrivelled version of herself. Her face had sunken around her tooth-gapped mouth, and she slurped shamelessly on her food and drink as a result. She smelt of dusty old skin, threadbare blouses and sour perspiration.

After dinner there was a sombre stint of listening to the ABC news on the radio for an hour, and then it was time to prepare for bed. Shirley helped Sarah undress and put on her hand embroidered nightie. Her hair was a stark, shiny silver and it spent everyday ignored in a pristine bun. At night it was released like a fossilised relic from a ruin – tumbling around her shoulders in a thin, eerie veil – longer and finer now that her frame was shrinking in size. Her grandmother sat imperiously on her bed holding out the silver hand brush that spent each day sulking primly on her dressing table.

‘Stand your ground girl!’ came the order – and young Shirley would commence brushing out the silver stream of hair with large clumsy strokes until it gleamed. It was a ritual that Sarah deeply enjoyed in her own stately way. Then she was helped into bed, propped up while Shirley prepared her ‘gruel’ for supper. This consisted of some pale, insipid oats boiled in water with a little salt and sugar. Sarah slurped her way through the bowl while Shirley prepared for bed herself, sleeping on a small divan in the corner. Summer or Winter, once Sarah had finished her bowl of gruel and belched ceremoniously, the lights were turned off within a minute or two of eight o’clock, and the night was over. Well … not exactly over for Shirley, who finding sleep elusive, continued to toss and turn on the uncomfortable divan for an hour or two afterwards.

The following morning at 6 a.m the alarm clock exploded, and Shirley would be ordered out of bed to get tea and toast. After helping Sarah dress and making the bed to her satisfaction, she was tipped out of the flat into the cold, dark streets. Catching the next train at Malvern station, she would find herself at Flinders Street at 7.30, an hour before the college even opened! It was a long, cold wait loitering on the busy morning pavement, but eventually the sisters would arrive to unlock the doors, and Shirley could get in out of the cold.

After a year of typing and cleaning the toilets, Shirley was definitely looking forward to a life of independent employment. She was lucky enough at the end of the year to be offered a job at Optical Prescriptions on the Bourke Street hill, and her first pay packet was a cause of great celebration for her and Lorna, who had also commenced her own typing career. Even after making her contribution to the family budget, Shirley felt the power of having her own money for the first time, and thriftily planned all the important purchases she needed to make.

The war also bought a new excitement to life – at least for the first year or two. The papers were full of valiant stories of successful campaigns, and disconcertingly strange maps of foreign countries. Posters appeared on street corners and in shop windows filled with the radiant faces of women in the land army, and muscly young men striding off to do their bit. It all seemed a strange new world. A few of the boys were itching to be old enough to get involved in the war, and were counting down the days until their 18th birthday. There were still plenty of boys who were in essential services and were required to stay put, so thankfully there weren’t too many impositions on the social life in Richmond.

On occasions throughout Shirley’s life, May’s relatives from Tasmania had ventured up to the mainland for a visit. She was their source of accommodation in Melbourne, and Richmond was a popular spot from which to experience the hubbub of a big city. South Franklin was about as different from the backstreets of Richmond as two places can be, and it would often be Shirley’s job to help the country folk around the busy streets of the city giving advice on either walking or taking a tram to where they needed to go, without being mowed down by vehicular transport.

Phillip Oakford, Shirley’s cousin from South Franklin, had enlisted in the Navy, and while he was waiting for his start at Flinders, and during his leave breaks, he would come and stay in Griffith Street. Shirley had met him and liked him as a little girl when he was a teenager in Franklin, and they got along well now too. He broke up the dynamics of the household, and there was someone to yarn to and joke with when he was on furlough. In 1941, his commission was about to start, and he discovered with great excitement that he was being posted to the HMAS Sydney. His brother, Les, had just completed a tour to Europe and Alexandria, including some famous victories at Calabria that made the front page of the papers. It was the prestigious pride of Australia’s fleet, and there were celebrations at Griffith Street the night before he left for service involving a special treat of roast meat and gravy, pudding, beer and rum. Two brothers could not be aboard the same warship, so Les came off the light cruiser to allow Phillip to go onboard, feeling quite chagrined to lose his place on this famous arsenal in the war.

They said goodbye the next morning at the train station. Phillip was wordlessly excited as he farewelled Shirley and May. Promising to write, he disappeared into the buoyant mass of sailors and soldiers boarding the train. Shirley felt a strange jealousy of the glamour and adventure of it all.

In the space of a month, Phillip was lost along with all 644 crew of HMAS Sydney. She sank alone and afire after a thirty minute battle with the German auxiliary cruiser Kormorant on evening of the 19th of November 1941, near Dirk Hartog Island off North-Western Australia. It took over four days for a search and rescue mission to be launched. The telegram arrived from May’s sister in Franklin a few days later, while Shirley was at work. When she returned home to the news, her mother’s bedroom door was locked. Shirley did not see her for a week.

The disastrous circumstances of the sinking of the Sydney was shrouded in secrecy for years. The rather unassuming news report above appeared on page seven of the Melbourne Age newspaper a full week after the Australian government knew of the loss. It took until the 1980’s for proper research of the tragic incident to be released to the Australian public. The wreck was finally found some 70 years later.

One thought on “Chapter 16”