Becoming Auntie Shirl

In early 1942, Shirley’s life was changed forever in a way that fate has of randomly picking up people’s lives and shaping them forever, just as the ocean washes a piece of reef off the beach and pushes and melds it in waves and storms so that it is shaped and smoothed into a sea gem, eventually returned to wreathe the shore. Nobody at the time could have realised this as the start of lifelong commitment for Shirley. It was births of her older sisters’ children.

Babies were something of a mystery to Shirley, being the baby herself for so long, and when her sister Lorna gave birth to the first grandson and nephew Jeffrey, the whole family were immediately besotted by the arrival of a boy in the family after all the years of girls. He was a happy, chubby baby and he crawled cheerfully around the cold hallway of Griffith Street bringing simple joy and laughter. He was quickly followed by another boy, David – somewhat less quiet and placid, with intense eyes and dark hair, who seemed to be in his own world a lot of the time.

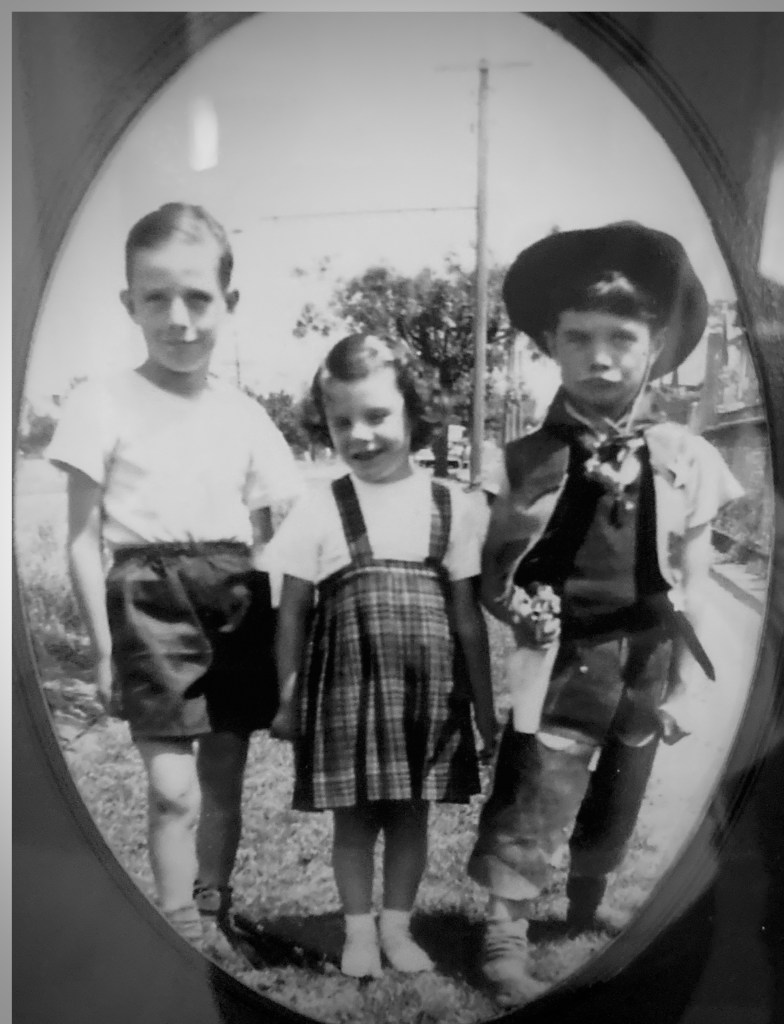

Lorna and George lived in George’s parent’s house in West Coburg and Shirley visited them every Saturday to dote upon her nephews, knitting them baby jackets and jumpers. When Lorna came to Richmond, Shirley would take the little boys out into the garden to visit the duck and to poke twigs through the chook pen enclosure. They were a delight. Jeffrey grew into a bonny, fat toddler who giggled every time Shirley sang to him, and David wandered around getting into mischief before anyone realised. She decided boys were much easier and happier than girls, and she set her heart there and then on having three boys of her own when she married. In 1945, a tiny girl joined the boys – Christine. She was regaled in the most elaborate layettes and her hair always trimmed with curls and bows – never leaving the house looking anything less than a baby bouffant princess. The boy’s shorts and jumpers started to take on something of an outgrown shabby appearance, and Shirley felt a little sorry for their relegation to consorts for their royal sister. She made even greater efforts to make a fuss of them when she saw the boys as a result.

So, through a haze of working at Optical Prescriptions in Collins Street during the day; avoiding going home to Griffith Street at night where Eileen and Bill were causing heartbreak and chaos; knitting socks for the war effort; spending time with Lorna’s children and at the Milton house – and missing Fred; 1944 and 1945 drifted slowly by. Parts of the world that Shirley could have barely imagined before the war became familiar now, and when battles Fred was involved with were in the papers it was a topic of great conversation, although Kate was someone to steer clear of in that case. She became somewhat hysterical at the mention of skirmishes HMAS Shropshire was involved in, and it was better to avoid her when details of naval battles made the news.

Each month or so, a letter would arrive from Fred. Sometimes there would be two in the space of a few days, and the arrival of Fred’s letters caused a huge range of feelings for Shirley. His neat florid script was impressive compared to Shirley’s own basic scrawl, and he wrote wonderful descriptions of some of the places they visited whilst being careful not to let on any ‘war secrets’. He shyly expressed to Shirley how much he missed her and looked forward to beating the Japs out of the Pacific so he could return home again in due course. There wasn’t much he could tell her about what was happening in the real world of naval battles, but he was always positive about the outcome of the operations, and that the Japs would soon be defeated and driven out. Fred wrote well and sometimes his descriptions of the faraway places that seemed so unimaginable to Shirley made her feel as if she was there. She felt rather inadequate when she wrote back rambling on about the local lads and lasses living their uncomplicated lives back in Richmond. It all sounded so boring and unreal.

Some of the ugly dramas that were unfolding in her own personal world as Eileen and Bill both tried to outdrink each other were her ‘war’ stories, but she kept them well hidden from everyone. They were shameful family secrets and ones she avoided, if possible, by spending every weekend with Thelma at the Milton’s house. She barely spoke of it to anyone, even her closest friends. She grew increasingly resentful of Eileen, but Bill became a glowering presence in the home that Shirley could not bear. Luckily, or unluckily for them all, after he got paid on Thursday, he would disappear until Monday night when he would return hungry, broke, and sober until Thursday’s wages/drinking and gambling money appeared at lunchtime on the job. If it weren’t for her mum and dad, her sister and Bill would have been homeless. Eileen’s increasingly disgraceful, drunken episodes filled Shirley with disgust and heart wrenching pity at the same time. She had witnessed the way Bill treated her sister, and the muffled beatings she had heard through the paper-thin walls of the Griffith Street house, were reason enough for Eileen’s growing obsession with grog. Yet the abject sight of her drunken sister appalled her.

The beginning of 1945 saw the birth of Shirley’s third nephew, this time to Eileen and Bill. Blue-eyed and blonde, bubbling with love and excitement when anyone passed his line of sight; Terence was a delight. Eileen managed to be a loving mother and for quite a long stint Shirley did not see her drunk. Bill was proud, and for a while he came home at a respectable time from the pub and did not disappear over the weekends quite as often. However, as the bonny wee boy grew and began to crawl around the house creating havoc, Bill once again disappeared, and the drinking and fighting recommenced. May felt heart achingly sorry for little Terry, and wrote notes apologising to him on the back of photos that she kept of him and his brother until she died. Inevitably, upon returning home from work, Shirley would find him in the sole care of her harrowed mother who was endeavouring to get tea ready in between holding the fractious child who was already needing his bedtime. Both Bill and Eileen would be nowhere to be found. Eileen, at least, would return from the hotel just after six most of the time, often in a state of drunken disarray, and Shirley’s mother would receive her with a stony silence that made the evening meal ritual more harrowing than it had ever been. On the worst nights, she would sway sickeningly to the table where she struggled to pick up the cutlery to bring the food to her mouth. So drunk was she one night that she passed out and fell face first into her corned beef and mashed potato. May screamed at her and she stirred. Arthur and May dragged her like a sack into her room. Terry started crying and Shirley tried to pacify him with a piece of bread and honey.

More things happened in the house then – she tried to frantically to forget them whenever she walked down the front steps and down the street. Her father buried himself even further into his library of literary giants and port wine; May’s trips to Tasmania became more and more urgently organised and longer in duration, and Shirley found any excuse to be out most nights of the week, so she did not have to think about what was happening or about to happen in this descent into alcoholic madness that was lived in Griffith Street every day. When Shirley did return home from work, Terry would often be wandering snotty nosed around the house, or the cold garden in his sodden nappy. If Eileen was there, she was asleep in the spare room, snoring soporifically. Finding some warm clothes, Shirley changed him, gave him milk, and sang him songs, while she peeled the potatoes for tea. That little boy had the bluest eyes, below sweet, sandy curls. The eyes of a Winter stream. He would not leave Shirley’s side while she put on the tea. Not until Arthur came through the door and tickled him before sitting down to eat. At some vague point of the evening, his mother would appear staggering to the table, then perhaps Bill his father may trudge down the hallway during dinner, if it was the night before pay day. By then however, Terry was often asleep in Shirley’s room at the foot of her bed, warm and breathing like a cat. He would wake her up in the morning and she would leave him with jam toast and milk before she had to hurry out the door to catch the tram to the city for work. Shirley would pinch the feet of her unconscious sister before she left, hoping to rouse her into motherly attendance before she had to leave Terry in the fireless house for the morning. She swallowed and bravely closed the front door. Her mother’s return from Tasmania could not come too soon.

At least during the day Eileen didn’t drink as much so there was someone to care for Terry. The poor little boy did not choose to be born into this. But nothing anyone could do made up for the beer running through his parents’ veins.

Soon enough, Terry was followed by a dark-haired, miserable baby – Anthony, and Shirley became adept at being able to sleep through a screaming infant. Without the help of May and of Shirley when she was home, those boys would have had little chance for a normal life. By the time Tony was walking, Eileen had sunk into a cycle of drinking that seemed to Shirley designed to beat Bill at his own game.

Shirley felt ashamed of her sister. Men – well everywhere she looked and nearly every father she knew – drank. They all got full every night. It was just life in Richmond. But the shame around women who drank and got drunk in public was against everything that the nuns and society had ever taught her. It was a terrible humiliation and embarrassment. Shirley hated Bill for what he had done to Eileen, and she hated Eileen for what she had done to herself, her boys, and to her mother and Shirley. She would never forgive her.